Pig Farming in Central Texas

Building Community One Twisted Fly Fishing Event at a Time

Two of the coolest fly fishing-related events you’ve never heard of are happening in San Marcos Sept. 26 and 28. To understand the shenanigans, let’s take a look at last year’s nuttiness.

I relaxed when Mark Crawford walked into Austin’s YETI Flagship Store, beer in hand.

It might have been the extravagantly waxed mustache sitting atop an unruly salt-and-pepper beard. Or maybe it was the black utility kilt he was wearing. Probably it was his broad smile when I answered that yes, this was where the fly-tying thing was happening.

I had never met the burly former soldier before, but it was clear from the very first moment that he was bringing the party with him.

Mark introduced himself to some nervous newbies, dragged out to the Thursday evening event by a co-worker. At a table in the middle of the room, Umpqua signature tier Matt Bennett talked shop with Onion Creek Fly Co.’s Wes McNew.

And behind the bar in YETI’s Custom Shop, ReelFly’s Donovan Kypke and Real Spirits head distiller Davin Topel joined emcee John Henry Boatright in sorting tying materials: pipe cleaners, chewing gum (“What do you think? One piece, or two?” Kypke asked.), miniature dolls with flowing hair and sequined gowns … it was a Dollar Store bonanza.

John Henry called me up to the stage to talk about Pig Farm Ink and why we were hosting this oddball gathering called Iron Fly. He did that because he knew that I couldn’t talk about it without getting a little choked-up.

Iron Fly 2019 happens Thurs., Sept 26, starting at 6 p.m. Click on the poster to enlarge.

He also knew that, along with everyone else in the room, I was attending my very first Pig Farm Ink event and had only the vaguest idea of what we were getting into.

For the Austin pig farmers, it started with a podcast. Jason Rolfe reading his story from The Flyfish Journal and interviewing film maker, Pig Farm Ink co-founder and actual (literal) pig farmer Jay Johnson. Johnson made the case that community matters, that fly fishing is a vehicle for building community with people from all walks of life, and that #flyfishingsaveslives.

Here’s the thing: Pig Farming is a bit of an ambiguous concept – something the founders (really, we should call them “instigators”) built in to the brand. Cancer survivors have Casting for Recovery. Veterans have Project Healing Waters. The rest of us – and cancer survivors and veterans, too – have Pig Farm Ink.

Since the first Iron Fly event in Fort Collins, Colorado, in 2011, fly fishing communities in more than 40 cities in three countries have thrown approximately 200 parties. The events have ranged from river cleanups combined with fly fishing tournaments to fly tying combined with karaoke (American Flydol) to the ever-popular Iron Fly events, modeled loosely on Iron Chef.

National sponsors include heavy hitters like Simms and Costa del Mar and PostFly, and the inaugural Central Texas events benefited from the generosity of the burgeoning homegrown community of outdoor heroes that includes Diablo Paddlesports, Howler Bros, YETI, Real Ale, Sightline Provisions and others.

The first, unwritten rule of every event is to suspend judgment and have fun. Alcohol is nearly always involved and breakfast beer is a thing. The last, written rule is this warning: “Irresponsible behavior will be loosely tolerated and asshats kicked directly in the face.”

The space between those two admonitions accommodates all sorts of shenanigans. It even accommodates some serious feels – moments of connection between people who only hours before were strangers.

By the end of the night at the YETI Flagship store, the noobs had tied some respectable San Juan worms and Clousers – fumbling through at least one, side-splitting round blindfolded. The experienced tiers whipped-up some Dollar Store Specials. A few of the flies incorporated dolls’ heads. One featured a partial denture.

A couple of Californians in town for the Austin City Limits Festival were shanghaied and took turns at the vises. One of the random visitors won a pair of Costa del Mar sunglasses. A bunch of anglers who knew each other only through social media posts met in person. A group of ladies, strangers at the outset, made plans for a women’s-only trip. Rideshare companies made a killing.

Saturday morning, some of the Iron Fly contestants and a whole bunch of other folks -- nearly 40 in all -- showed up at Reel Fly’s Canyon Lake shop for Get Trashed on the Guad. Crawford, who had swapped the kilt in favor of wading pants, brought his entire family, and together they picked up 34 bags of trash. Probably (but not certainly) fewer than a third were filled with their own empties (the rules specify that your own beer cans count).

Turns out that scouring a river for trash is thirsty work.

One angler caught and released a beautiful, 23-inch holdover rainbow trout. Another guy, who had tied his first fly Thursday evening caught his first fish on the fly, ever, and won a handcrafted wooden landing net from Heartwood Trade. Fifth-grader Ethan Wu held the lucky raffle ticket for a Traeger Grill, much to his father Odom’s delight. A couple of people, including me, fell on their asses in the river, to everyone else’s delight.

Get Trashed on the San Marcos kicks off at 8 a.m. Saturday, Sept. 28. Click on the poster to enlarge.

Everyone appeared to be just a little surprised at how much fun they had.

“I kind of liked the veil over both events. You have an idea of what it’s going to be, and people have an idea of what they’re going to be doing when they show up, but it’s just a little different, a little twisted,” said organizer Donovan Kypke, who was also celebrating his first anniversary as the owner of ReelFly Fishing Adventures. “When they got there and realized it wasn’t about competition, people really relaxed and partied and ran with it. The amount of freaking trash we got out of the river – I had no idea it was going to be that scale.”

Davin Topel, the distiller and fishing guide, hosted event planning sessions at the Real Ale brewery and distillery in Blanco, Texas, over the summer. He said that the Pig Farm Ink events serve as a useful reminder that fly fishing is a sport for everyone.

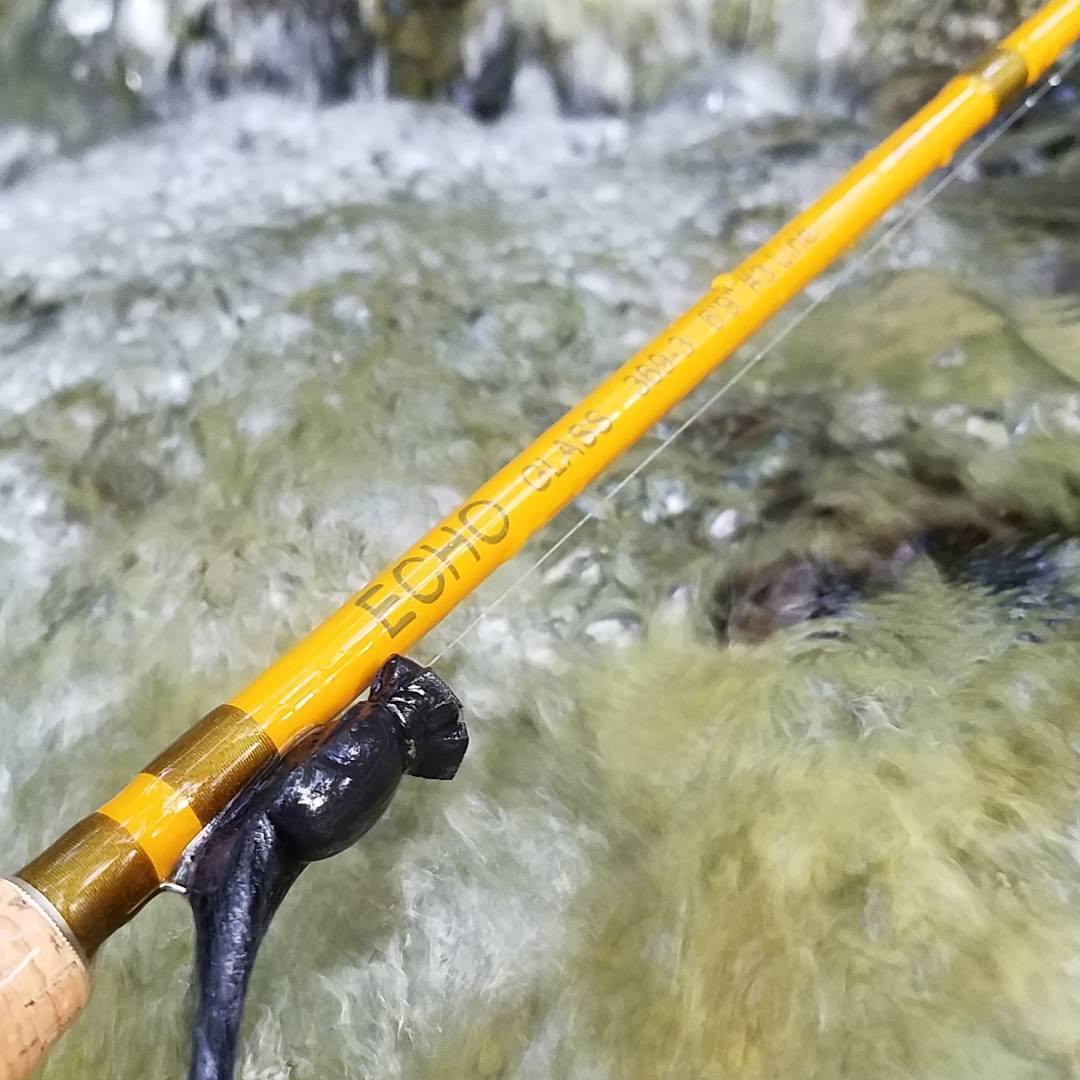

“It’s not just for old, white guys who have too much time on their hands and like to argue whether or not a mop can be used as a fly,” he said. “Life is complicated enough; your hobby doesn’t have to be. Just grab a rod and go for a hike with your friends. And don’t forget the whiskey.”

Iron Fly 2019: Thurs., Sept. 26, 6 pm—Bitchin’ at Sean Patrick’s in San Marcos

Get Trashed on the San Marcos: Sat., Sept. 28, 8 am—6 pm, Texas State Tubes, San Marcos

Photos courtesy Merrill Robinson.