So, you want to get into fly fishing ….

Someone just gave you a gift card, or maybe you got a Christmas bonus and figure: Hey, it’s time to check out that fly fishing thing.

You start poking around on the interwebs. Probably you search for “best fly rod” or “best beginner fly rod.” You are quickly overwhelmed by a bewildering array of choices.

It’s a good thing. Truth is, never in the history of mankind have there been more choices of really good gear at reasonable prices. With only a few exceptions, our best “budget” rods today are better than the most expensive rods our parents or grandparents could buy 30 or 50 years ago.

Now … you’re probably wondering: where to start? Visit your local fly shop! Seriously. Fly shops are cultural centers as much as retailers, and the people who own them and work in them care about the sport and care about building a relationship with you, the new (or new to fly fishing) angler.

Good fly shops – and most of the fly shops that stay in business more than a couple of years are good – also are excited to meet folks new to the sport. Don’t be afraid to admit what you don’t know, and don’t be intimidated. Heck, you probably won’t even run into anyone actually wearing tweed.

If you don’t have a local fly shop, or if you want to go in with a bit of background knowledge, keep reading.

In fly fishing, it’s all about the rod. The reel is, for the most part and for most target species, just a line holder. More about reels in a bit. Fly line is the third integral part of the outfit, and is meant to last a season or two, and is priced accordingly, but there are some good, inexpensive options out there.

Fly rods are labeled by weights, from 000 on the super-ultralight end to 14 or so on the really heavy end. Most folks use rods between 3-wt and 8-wt. Many anglers recommend a 5-wt as a good, versatile, compromise size. I hold the minority opinion that 5- and 6-wt rods are overkill for most situations you’ll encounter in Central Texas; unless you are specifically targeting big carp or stripers, or pulling lake-dwelling bass from heavy cover, a 2- to 4-wt should be able to handle everything and will be a lot more fun and less tiring over a day-long session.

As an example, even though I am somewhat fitter than TV celebrity Larry King, as I enter middle age I find that I’m good for about 2 hours on an 8-wt, but can swing a 2-wt or 3-wt sunup to sundown and still lift a pint glass without discomfort.

My recommendations at the end of this explainer tilt toward ultralight (3-wt and below) rods because that’s what I fish 90 percent of the time. I didn’t always, and I still own heavier rods, but I rarely reach for them. Generally, I believe most anglers “over-rod” for the waters and species they are targeting. Your mileage may vary, and others will definitely have different ideas.

My recommendations also tilt toward less expensive equipment, generally. Look at the title of this site. I have a good idea, to within a dollar or so, how much the material in most imported fiberglass and graphite blanks costs ($5). I know, to within a couple of dollars, how much a complete graphite rod costs wholesale from an Asian manufacturer ($20-$60, depending on the model and components). And I know that those rods are sometimes painted a different color, re-labeled, and marked-up as much as 500-1,000 percent for the U.S. market, sometimes by brands you would recognize. Not even kidding.

Don’t get me wrong; I like nice stuff — who doesn’t? More importantly, I like stuff that works and doesn’t make me work any harder than I have to while I’m using it. On the one hand, I like to support working men and women with a living wage. On the other hand, I’m also a working man and I don’t appreciate feeling I’m being taken advantage of.

Chances are, if I have a choice between a very good $200 rod and a truly great $800 rod, I’m gonna save $600 and spend it on a week-long roadtrip through the mountains of northern New Mexico and southern Colorado. It’s a matter of priorities. I won’t make fun of yours if you buy those $160 nippers, but I am going to wonder a little.

Rod weights correspond to line weights – measured in grains — of the head or first 30 feet of a fly fishing line. The American Fly Fishing Trade Association (formerly the American Fishing Tackle Manufacturers Association) publishes a handy table that says what the standard is.

There has been significant creep in recent years, mostly as a result of faster, stiffer, lighter blanks; the result is that some rods are labeled as, say, a “6” when in reality they are 7s or even 8s. Some line manufacturers have responded by increasing the actual weights of their rated lines … others are more honest and will tell you right on the packaging that the line is a half weight (or more) heavier than the number they slapped on there. The end result is that, often, you will have to try several lines on a given rod to find one that works well. Don’t assume your rod is crap until you’ve mixed-and-matched a bit. Alternatively, scour online forums or talk to fly shop pros about which lines work with which rods.

When choosing a rod, your first consideration should be: what size flies will you be throwing, and next: how much wind are you dealing with? The weight of your line (and thus the size of the rod) will determine how well you can handle big flies and big breeze. A secondary consideration (though it’s related to the size flies you will be casting) is how well you can deal with big fish, or, what species you will target.

There is an argument sometimes made that ultralight rods contribute to post-release mortality by excessively tiring a fish. The opposite may actually be true, as an angler can more confidently play a fish on lighter gear that protects the tippet.

Rod length is less important unless you are engaged in technical Euro-nymphing (don’t get too excited, it’s a fishing method), two-handed spey casting, or you are fishing small, brushy streams. Many manufacturers default to 9’ lengths and that’s fine. I fish a lot of smaller streams with lots of trees, and the only 9’ rods I own are one legacy 4-wt and several 8-wts I deploy against redfish and snook. I own 8′ and 8.5′ rods, but the ones I use most often are between 6.5′ and 7.5′ and my shortest fly rod is 5’9″.

The number of pieces a rod comes in also is relatively unimportant. Experienced conventional anglers may frown on multi-piece rods as “unserious,” but the very best rods in the fly fishing world happen to be multi-piece. Four-piece rods are standard and pack down small enough to put in luggage. Three-piece rods are common, especially in fiberglass models, and there are a number of 2-piece rods in ultralight weights, and up until the advent of graphite, many production fiberglass rods were made in two or three pieces. They still work just fine. One-piece rods are uncommon

You have choices in rod material, which boil down to, essentially: glass, graphite, or bamboo. Good cane rods are works of art and are quite expensive, so scratch bamboo as a starter. Fiberglass, which burst on the scene as a “modern” and less-expensive advancement over bamboo after World War II, is experiencing a resurgence and many say we are in a new “Golden Age” of glass rods.

Glass rods typically (but not always) are slower and more full-flexing than graphite and a lot of anglers enjoy being able to feel the rod load. That characteristic also is helpful to new anglers when learning to cast. Glass rods (and slower rods in general) excel at short- to medium-range casts (which is where you’ll do most of your fishing, realistically) and typically roll cast more easily than faster, stiffer rods. Some anglers say glass rods have more “soul.”

Graphite, or carbon, rods come in many flavors – from full-flexing low- or multi-modulus models that mimic traditional glass or bamboo actions to super-fast, high-modulus, nano-particle-infused rockets designed to generate insane line speed over long distances. The trend in recent years definitely has been toward the latter, which may not serve you — the person just starting-out — all that well. In-between, you’ll find many rods described as all-arounders, labeled as “medium” or “medium-fast,” and that’s probably a good place to start if you opt to get going with graphite.

You may discover, in test-casting prospects (and you should definitely do that if at all possible) or as you begin fly fishing in earnest that you have a particular “style” of casting that you are most comfortable with. I like a slower, more relaxed stroke and favor medium and slow action rods. A good friend of mine, a very good caster who fishes rods in the same weights, really likes a fast, crisp action and is always on the lookout for the stiffest 2 wt he can find. All that said, you’re not locked into one or the other, just realize that as you switch back and forth between your slower rods and faster rods you’ll have to adjust your stroke and it may be ugly for a couple of casts if you are not paying close attention. I speak from experience.

Where is the rod made? Some folks obsess over this, but from a performance standpoint it is unimportant. If supporting American manufacturing jobs is high on your list of priorities, then consider saving your money for a Scott, Sage, G. Loomis, Thomas & Thomas, R. L. Winston or high-end Orvis or St. Croix fly rod. With few exceptions, all other production rods are made overseas. For the past three or four years, the rod judged one of the five best in the world, with an $800 price tag and offered by a venerable English maker, was sourced in Asia.

Rods built overseas include models by well-known brands such as Redington, Orvis (some models), TFO, Echo, Hardy, Loop, Fenwick, Cabela’s, White River (Bass Pro), Allen and so on. Buy one of those and you are supporting jobs in a foreign land, but design, marketing, warehousing and retail jobs in the USA. Keep in mind that your smart TV, Apple or Android device, and quite possibly your dependable, well-designed vehicle all come from the same places.

Then you have the “Chinese knockoffs,” which may or may not be knockoffs (or from China). Some overseas manufacturers have been building rods for the companies above for close to two decades now and they’ve developed a bit of in-house expertise. What you may not get from these companies, if you buy their version or a private-label version, is the level of customer support or warranty service you are looking for. But, then again, you might. I’ll highlight a couple of good bets in a moment.

Learning to cast a fly rod is not, exactly, like learning to cast a spinning outfit or a baitcaster. It’s a process, and something most of us continue to work on for a long time. It’s more like … developing a tennis stroke or a golf swing, maybe. You can become proficient enough to catch fish and have fun after the first hour or half day of practice, but you may still be refining your technique or adding new casts the last time you pick up a fly rod. I mean, like, right before you die. It’s one of the great joys of a sport that – for me anyhow – has so far proved to be bottomless. I’ll never get to the end of it, and I kind of like that.

Orvis company stores offer free Fly Fishing 101 classes spring-fall. Orvis also offers a terrific, streaming video introduction broken down into bite-size segments. Your local fly shop, if you are fortunate enough to have one, probably does something similar.

My local fly shop, Living Waters Fly Fishing in Round Rock, offers a free, half-day “Introduction to Fly Fishing” at least one Saturday a month, covering everything from how to cast to which flies to use to where to fish. It’s worth driving in from out-of-town to attend and you would be welcomed more than once, though you are allowed to eat the complimentary Round Rock donuts only the first time. Just kidding.

Your local Fly Fishers International (formerly Federation of Fly Fishers) club probably offers casting clinics, or at least practice sessions before monthly meetings, and may have members who are FFI-certified casting instructors. There are 170 of these clubs across the U.S.A., 17 in Texas alone. Colorado has five. At the very least, your local club will have some members who are happy to mentor a new angler.

Buy the best gear you can afford now. Sometimes $800 fly rods cost $800 because a lot of time and effort went into their development, they use top-quality components, and are backed by excellent warranties and customer service. Fit and finish, typically, is outstanding. Your kids will fight over them after you are gone. Maybe before then.

In a few instances, those heirloom rods cost that much only because the companies are paying for American labor, have high overhead otherwise, and have figured-out people will pay through the nose for perceived status symbols. On balance, I would say that you are less likely to be unpleasantly surprised by an expensive rod from a reputable manufacturer than by a no-name cheapo rod.

That said, there are lots of really, really good rods at lower price points these days. More than one fly caster much, much better than me has said that the differences in performance between the best “budget” rods and the best rods at any price are all but indiscernible to anyone other than a competition caster. That is, the likes of you and I are never going to see that last 10 feet of distance or 10 inches of accuracy in our casts.

As you grow in the sport and discover a preferred casting style and quarry and the kinds of waters you most like to fish, you can narrow-down the kind of rod that works best for you. (This is an argument for that 4-wt to 6-wt, range to start with, by the way.) That’s the time to start thinking about dropping big bucks for a higher-end, or even custom rod. For me that means a C. Barclay Fly Rod Co. Synthesis 68L (3-wt) or 66 (2-wt), or something from Shane Gray or Matthew Leiderman. It may mean something else for you.

Concrete recommendations for terrific value rods that I have used, friends love, or are well-reviewed (or all three) include:

1. TFO Finesse, $199. Half-weight through 5wt. Slow, full-flexing graphite. Lifetime warranty. Texas company (manufactured in its own factories in S. Korea). My pick: the 1wt or 2wt for Guadalupe bass, Rios, sunfish, and wild cutthroat in high mountain streams. (note: since this was originally written, TFO discontinued the original Finesse line and introduced something called the “Finesse Trout” at a slightly higher price point. Weights and lengths are the same; no report yet on whether the actions are too.)

2. ECHO Carbon XL, $149. 2-wt through 6-wt. Medium-fast action. Lifetime warranty. Designed by Tim Rajeff. Vancouver, Wash., company. My pick: the 2-wt for everything (this is my go-to graphite rod), 3-wt for bigger fish or windier days. I have friends whose go-to rods are the Echo Carbon 4-wt or 5-wt and they love them.

3. TFO Pro Series II, $170, 2-wt through 10-wt. Medium-fast action. Lifetime warranty. My pick: the 7’6” 3-wt for Central Texas streams. Note that this is not the same model as the Lefty Kreh Signature Series II, which sells for a little less and is quite a bit less capable.

4. ECHO Boost, $229, 2-wt through 10-wt. (Really) Fast. Lifetime warranty. The 2-wt is a favorite ultralight of the guys at Rajeff Sports, the parent company of Echo Fly Rods. Designed to generate “maximum line speed with minimum effort,” the 9’, 7-wt might be a good choice for the salt, for big carp, or windy days. May benefit from being overlined.

5. TFO BVK, $250-$300, 3-wt through 10-wt. Fast. Lifetime Warranty. Designed by Lefty (Bernard V.) Kreh. This design has been around for a while. I’ve had the 8 wt. for ages and use it for redfish and snook. Fast and light. A friend really likes the 4wt. for freshwater.

6. TFO Clouser, $210-$230. 5-wt through 10-wt. Described as fast, but more medium-fast – slower than the BVK, for sure. Lifetime warranty. Designed by the legendary Bob Clouser. I and a few buddies have the 8wt – it’s my go-to rod for saltwater. It’s also one of the prettier rods in the TFO lineup.

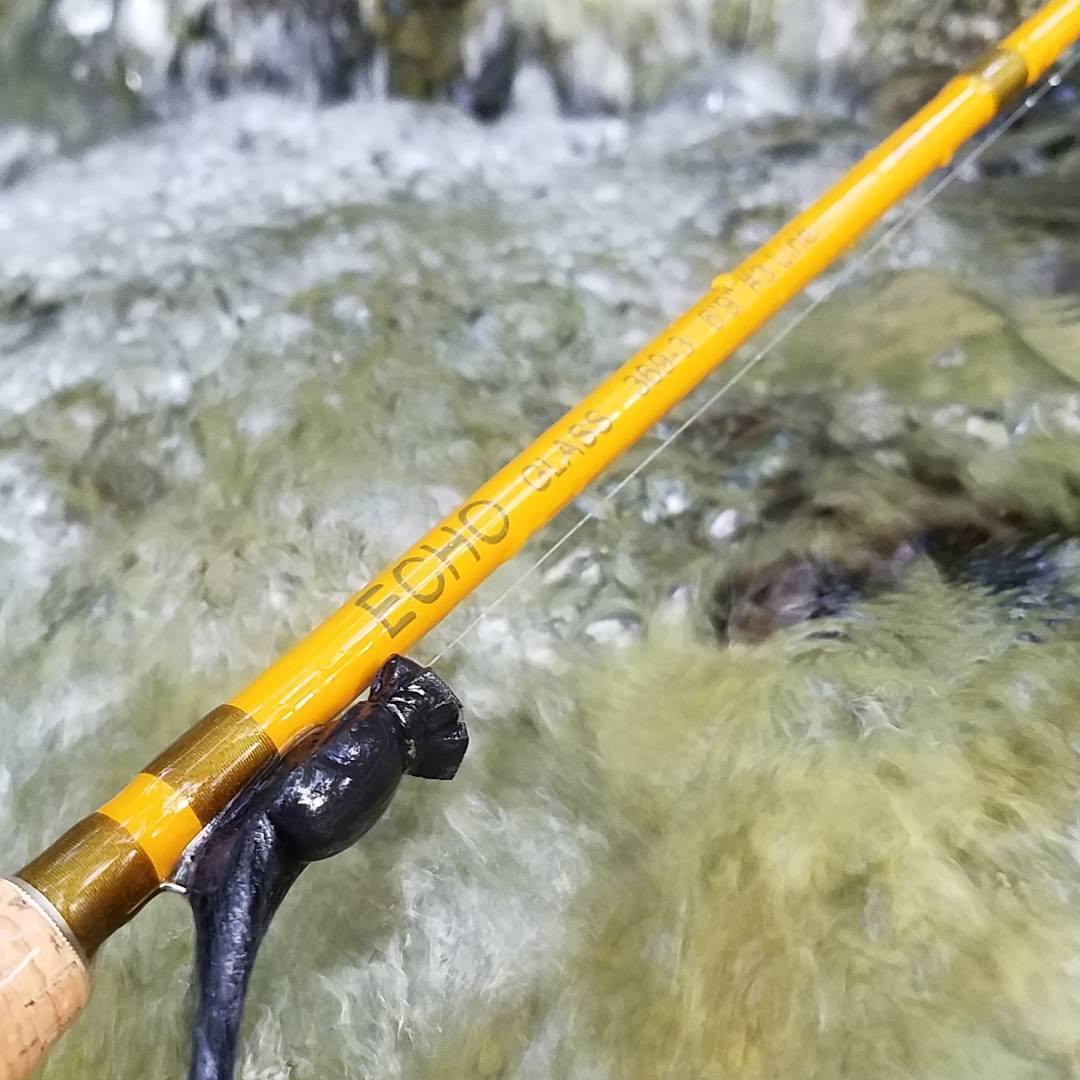

7. ECHO Smallwater Glass, $200, 2-wt through 5-wt. Progressive, deep-loading, medium-action rods. Lifetime warranty. Another Tim Rajeff design, my 3-wts (I have two) are sweet casting, small stream rods that can handle plenty of fish. They’re also pretty. (Note: These have been replaced, since this post originally appeared, by the ECHO River Glass series. Reports are that they are even better than the original glass rods.)

8. Cabela’s CGR, $69 (on sale for less several times a year), 2-wt through 7/8-wt. Full flex, traditional glass. So slow they are “noodly.” Lifetime warranty. The 2-wt and 3-wt are a TON of fun on sunfish and small bass, and excel at casts to about 40 ft. Worth every penny of the regular price, a steal when on sale.

9. Maxcatch V-Light, $59, medium-fast, 1-wt through 3-wt. Limited warranty. Sometimes marketed as “Ultra Lite for Panfish and Trout.” The parent company of Maxcatch, headquartered in Quingdao,China, makes rods for a number of major brands and private labels, some very well-reviewed. Having tried half a dozen of their models, the ultralight 2-wt is a real gem. I’ve had bad luck with the 3-wt in the same series, with tip sections breaking for no good reason on four different rods. I can’t speak to the heavier rods, but some may be just fine.

10. Aventik “Super Fiberglass” Fly Rod, $79-$99, 3-, 4- or 5-wt. Medium-action glass. 25-year warranty. The identical rod also is marketed as a private label rod, the “Ruby River,” and has been well-reviewed on The Fiberglass Manifesto and elsewhere. I have the 3-wt, and overlined with a standard WF4F it is a joy to fish. It handles a standard 3-wt line well, too.

11. Fenwick Aetos, $190, from a 6′, 3-wt through a 15′ (!) 10/11-wt. Fast action. Limited Lifetime Warranty. Fenwick is one of the great “blue collar” brands from the glory days of glass. I include the Aetos here because, if you are going to go with a 5-wt, this is the one that has taken top honors in its price range at the Yellowstone Angler Shootout multiple years. (Update: I recently had the opportunity to cast the Aetos 3-wt, and it’s just lovely.)

12. ECHO Base, $89-$99, 3-wt-8-wt. Medium-Fast. Lifetime Warranty. The Guys at Yellowstone Angler also like this rod, a lot. Everyone who has cast one or even just held it marvels that you can get this much rod for that little cash. It’s really a no-brainer if you are just getting into the sport. Or even if you’ve been at it a while.

You probably won’t be suprised to hear that fly rods tend to reproduce when you are not paying attention (or, more accurately, when your spouse or significant other is not paying attention). This is, generally, a good thing.

Fly reels reproduce at a slower rate. Reels typically can handle a range (usually three line weights, like 4 to 6-wt) of lines and can easily be swapped between rods, and you can buy spare spools for most reels at about half the price of the entire reel, putting a weight forward floating line on one and a sinking line on another, or a 4-wt line on one and a 5-wt line on another ….

Reels, as mentioned earlier, are perhaps the least important member of the rod-reel-line trinity. Unless you are protecting light tippet, get surprised as you are picking up your line, or hook a really badass fish, most anglers targeting most species won’t often play a fish on the reel. Exceptions include redfish, carp, steelhead, salmon, bonefish, tarpon, snook and pelagics, like false albacore. For those ,you want a good disc drag. For much of the rest, the reel is a line holder.

For reels up into the 5/6-wt range, traditional click-and-pawl (“clicker”) drags work just fine, and a palmable rim (the traditional way of applying drag) is added insurance.

Vintage examples that work just fine can be had on the big auction site for $25, and terrific modern ones for under $100. Nearly all modern reels are reversible – that is, they can easily be changed from left-hand wind to right-hand wind. Most leave the factory set-up for left-hand retrieve these days (50 and 80 years ago, the opposite was true; someone should explore why that is … ).

If primarily or even regularly using your reels in saltwater, you may want forged (not cast) aluminum with a hard anodized finish and a sealed drag. An exception to this is the Redington Behemoth reel, which is just pretty amazing for $109-$119. Available in sizes from 5/6 to 11/12, the Behemoth has an excellent drag and is an example of new pressure casting techniques that result in much smoother surfaces than the older cast reels.

For a traditional click and pawl reel, it’s hard to beat the Orvis Battenkill, available in five sizes covering 1-wt to 11-wt, for $98-$149. The Redington Zero is another popular clicker, offered in 2/3 and 4/5 for $90. Sage, Nautilus, Ross, Lamson, Galvan, Hardy and – as mentioned, Hatch – are reputable, high-end reel manufacturers. I’ve recently grown attached to 3-Tand’s TF-20 and TF-40 reels for my 2- and 3-wt rods. They’re pretty, sturdy, and with a sealed drag (I don’t really need the drag, but it’s nice to have), virtually maintenance-free. You also have tons of choices in private label and overseas-manufactured reels, some of which are quite good. More esoteric choices include Danielsson – the guy who invented the “large arbor” for Loop in the 1980s, and Vosseler, a German manufacturer that makes finely machined reels at very reasonable prices. Each of those designs take a slightly different approach to tensioning the spool.

Speaking of arbors (the diameter of the center of the spool), the major difference between a large arbor reel and a mid- or small arbor reel is the amount of backing you can (or will need to) put on the spool. Once you have added a sufficient amount of backing, a mid-arbor reel becomes a large arbor reel. In other words, don’t sweat it. The amount of line you can pick up in one revolution of the spool is not terribly important.

When it comes to lines, for the species and waters we fish in Texas, anyway, a weight forward floating line (often designated WF#F) is pretty standard. Some folks prefer double taper (DT#F) lines for specific applications or rods, or sinking lines or sink-tip lines (WF#S, etc.). Fly lines are manufactured with different coatings, from super slick to textured, for hot weather and for cold water. They can be expensive – more than $100 for some, $70-$80 for most. Many inexpensive fly lines are absolute crap and will do nothing but frustrate you. Two that aren’t crap and won’t make you unhappy: Bozeman Flyworks lines, and Maxcatch weight forward lines. Relative newcomer (and US-based “mom and pop” business) 406 Fly Lines makes a terrific double taper fly line ($69) that has worked really well on my ultralight glass rods. Among the big name lines, I’ve had much better experiences with Scientific Anglers than with Rio, but your mileage may vary.

By the way … you do know that a “fly line” is actually some amount of backing — usually 20- or 30-lb dacron — which is attached to the reel; the fly line itself, usually 100′ but sometimes 80′ or 90′; the leader, which can be be level or (preferred, usually) tapered, furled or extruded or knotted, purchased or tied by yourself, nylon or flourocarbon or dacron; and the tippet, the thin end of the leader, which can be renewed or added to repeatedly by using a tippet ring or tying line-to-line knots … you know that, right? Only the actual fly line is what your average person would consider spendy.

Other stuff you might need or want on the water includes a fly fishing vest or sling pack (but a large shirt pocket also works), a rubberized landing net (hand-landing or beaching most species is a simple matter, but a smooth, rubber net is much easier on the fish), hemostats or pliers to remove flies, spools of tippet, flies and a fly box of course … really that’s about it. You’ll want waders in the colder months, most places. You can find decent, breathable waders for $150 or less.

If you are coming to fly fishing from the conventional gear world, fly rods are – in one sense – just another tool. Everything you have learned about fish and fishing so far will help you. Trout are still lying in the same places, bass will still erupt on fly patterns pretending to be the same critters your lures mimicked, and so on.

In another sense, fly fishing more than any other form of angling can be a sort of mystical journey that, if not in itself a philosophy, has an awful lot of philosophy in it. It also has, as (again) Lefty Kreh pithily said: “More B.S. than a Kansas City feedlot.” For example: you thought that round, orange thing was a “bobber,” didn’t you? C’mon, admit it. Well, I’ll have you know it is not a bobber, it’s a “strike indicator,” or just “indicator.” Really. But … also, not really — it’s a bobber.

Like that.

Shrug that crap off. Be patient with yourself as you ease (or jump) into the sport. Find some guys or gals who have been at it a while — more than likely, they’ll be happy to help you out. And whatever you do, have fun!

Welcome. I hope to see you on the water sometime.